The human immune system has an extraordinary ability to remember past infections. Long after a virus or bacterium has been cleared, the body retains a cellular record that allows it to respond faster and more effectively if the same pathogen returns.

This ability to “remember” previous infections is known as immunological memory, and memory T cells play a central role in this process. Memory T cells, a specialized subset of T lymphocytes, enable the immune system to mount a rapid and powerful response upon re-exposure to a familiar threat, often preventing the risk of reinfection.

During an infection, antigen-specific T cells undergo activation, massive proliferation, differentiation into effector cells, and ultimately a carefully regulated contraction phase. From this dynamic process, a stable population of memory T cells emerges. These cells preserve the immunological “experience” of prior encounters and ensure rapid immune recall. Understanding how memory T cells arise from naïve immune cells after infection not only explains why we rarely get the same disease twice but also highlights modern vaccine design and immune-based therapies.

Before exploring the process of memory formation, it is helpful to briefly review where T cells originate and how they become activated.

Overview of T Cells and Immune Memory

T cells are a type of white blood cell (lymphocyte) that are key components of the adaptive immune system.

T cells recognize pathogens using specialized surface proteins called T cell receptors (TCRs). Each T cell expresses a unique receptor that allows it to recognize only one specific antigen. This remarkable specificity forms the foundation of immune memory.

Although many types of T cells exist, memory T cells arise primarily from activated CD4⁺ helper T cells and CD8⁺ cytotoxic T cells.

Step 1: Antigen Exposure and Naïve T Cell Activation

Where T Cells Come From

T cells are produced in the bone marrow but undergo maturation in the thymus, where they are educated to recognize foreign antigens while avoiding self-reactivity. Once mature, naïve T cells circulate through lymph nodes, spleen, and other lymphoid tissues in search of their specific antigen.

At this stage, naïve T cells have never encountered a pathogen. Their activation marks the first step toward both immediate immune defense and future memory formation.

Antigen Presentation Begins the Process

When infection occurs, specialized immune cells known as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells and macrophages, engulf pathogens through phagocytosis. These cells process microbial proteins into small peptide fragments and display them on their surface bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules.

APCs then migrate to nearby lymph nodes, where they interact with circulating naïve T cells. If a T cell’s receptor precisely matches the displayed antigen, binding occurs. This interaction provides the first activation signal.

However, antigen recognition alone is not sufficient to fully activate T cells. Additional co-stimulatory signals, such as CD28 engagement with B7 molecules on APCs and inflammatory cytokines, are required to confirm the presence of real immune danger.

Step 2: Clonal Expansion and Effector T Cell Differentiation

Once fully activated, antigen-specific T cells undergo rapid division in a process called clonal expansion. From a single naïve T cell, thousands of identical daughter cells are produced, all capable of recognizing the same pathogen.

Effector T Cells and Immediate Protection

Most of these newly generated cells differentiate into effector T cells, which carry out the active work of the immune response:

- CD8⁺ effector T cells directly kill infected or abnormal cells.

- CD4⁺ effector T cells release cytokines that coordinate immune activity, stimulate antibody production, and enhance pathogen clearance.

Effector T cells are highly effective but metabolically demanding. They are designed for short-term action and do not persist once the infection has been resolved.

At this stage, the immune system is focused on eliminating the immediate threat. Memory formation occurs later, as the response begins to wind down.

Step 3: The Contraction Phase- Restoring Balance

After the pathogen has been successfully cleared, the immune system enters a contraction phase. During this period, the majority of effector T cells undergo programmed cell death, or apoptosis.

This reduction in T cell numbers is essential. Without contraction, prolonged immune activation could lead to tissue damage or autoimmune disease.

Selection of Memory T Cells

Importantly, not all antigen-experienced T cells die during contraction. About 5-10% of the expanded T cell population survives and transitions into long-lived memory T cells. These cells possess unique characteristics that allow them to endure:

- Increased sensitivity to survival cytokines

- Enhanced metabolic efficiency

- Stable genetic and epigenetic programming

This selective survival explains why memory T cells are derived from activated effector cells rather than directly from naïve T cells.

Step 4: Formation of Memory T Cells

Cytokine-Driven Survival

The persistence of memory T cells depends heavily on cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-15, which provide continuous survival signals even in the absence of antigen. These cytokines support slow homeostatic proliferation, allowing memory cells to maintain their population over time.

Unlike effector cells, memory T cells do not require constant stimulation to remain alive. This ability allows them to persist for years or even decades.

Epigenetic Programming and Rapid Recall

Memory T cells undergo lasting epigenetic changes that keep key immune genes in a “ready” state. Because of this pre-programming, memory cells can rapidly produce cytokines or cytotoxic molecules upon re-activation without needing extensive re-differentiation.

This molecular readiness explains why secondary immune responses are faster and stronger than primary responses.

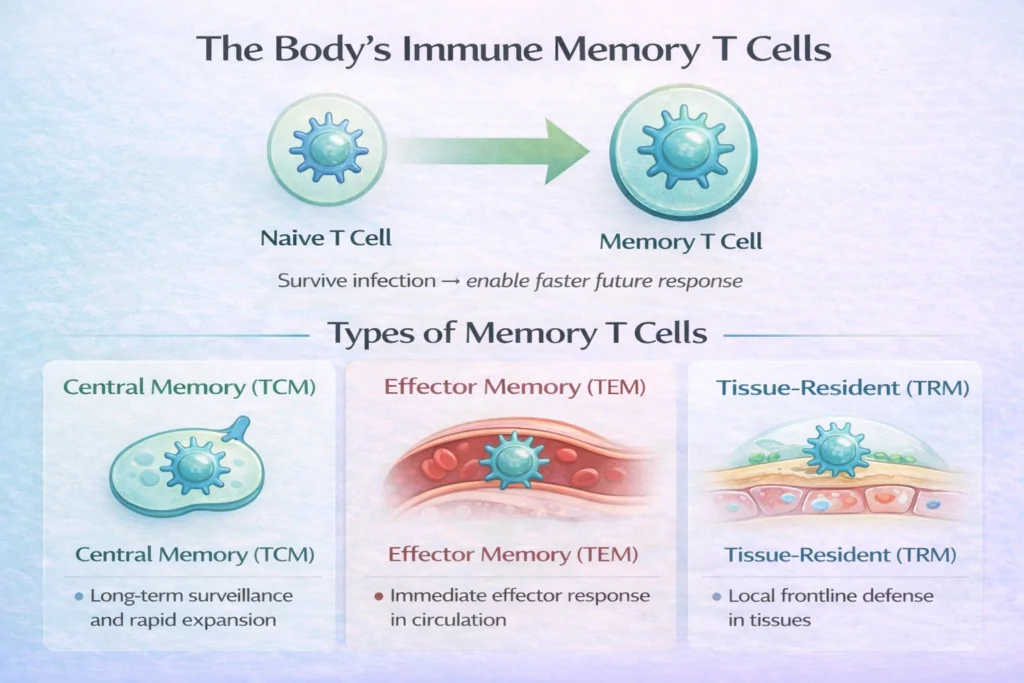

What are the Types of Memory T Cells?

Memory T cells are not a single uniform population. Instead, they differentiate into several functional subsets based on their location and behavior.

Central Memory T Cells (TCM)

- Circulate between the blood and lymphoid tissues

- Express lymph-node homing receptors such as CCR7

- Exhibit strong self-renewal capacity

Central memory T cells provide long-term immune surveillance and can rapidly expand into effector cells during reinfection.

Effector Memory T Cells (TEM)

- Circulate through peripheral tissues

- Respond quickly with immediate effector functions

- Play a key role in early pathogen control

These cells act as a rapid-response force, particularly in tissues commonly exposed to infection.

Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells (TRM)

- Permanently reside in non-lymphoid tissues such as skin, lungs, and gut

- Do not re-enter circulation

- Provide immediate local immunity

TRM cells are especially important for protecting barrier surfaces, where many infections first occur.

Step 5: Immune Recall and Secondary Responses

The defining feature of memory T cells is their ability to mount a rapid secondary immune response. When the same pathogen reappears, memory T cells recognize the antigen almost immediately.

Instead of requiring days for activation and expansion, memory cells respond within hours. They rapidly proliferate, differentiate into effector cells, and eliminate the pathogen before it can cause significant harm.

Cytokines and Memory Maintenance

Even during periods without infection, memory T cells remain active participants in immune homeostasis. Cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-15 continuously support their survival, confirming that memory cells remain functionally connected to the immune environment.

Bystander Activation

In some cases, memory T cells can be activated indirectly by inflammatory signals, even without direct antigen recognition. This phenomenon, known as bystander activation, can contribute to early infection control but may also trigger autoimmune conditions and chronic inflammation if poorly regulated.

Memory T Cells vs Memory B Cells

Both memory T cells and memory B cells contribute to long-term immunity, but they serve distinct functions:

- Memory B cells rapidly produce antibodies upon re-exposure to the antigen

- Memory T cells coordinate cellular immunity and directly eliminate infected or abnormal cells

Together, these systems ensure comprehensive protection against previously encountered pathogens.

Final Thoughts

Memory T cells represent the immune system’s ability to learn from experience. Through antigen exposure, activation, clonal expansion, contraction, and memory formation, these cells preserve vital information about past infections.

Their longevity, rapid responsiveness, and adaptability make memory T cells essential for vaccine effectiveness, protection against reinfection, and immune surveillance throughout life.

In essence, memory T cells are not simply remnants of an immune response. They are long-term guardians, quietly persisting, constantly prepared, and ready to act when familiar threats return.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the function of the memory cell?

The primary function of memory cells is to enable a faster, stronger immune response when the body encounters a previously recognized pathogen.

What are memory T cells derived from?

Memory T cells arise from a small fraction of activated effector T cells that survive the contraction phase after an infection is cleared.

Are central memory T cells CD4 or CD8?

Central memory T cells can be derived from both CD4⁺ helper T cells and CD8⁺ cytotoxic T cells, depending on the original immune response.

What are memory T cells vs memory B cells?

Memory T cells drive cellular immunity by coordinating immune responses or killing infected cells, while memory B cells provide humoral immunity by rapidly producing antibodies upon re-exposure to an antigen.

Why do memory T cells respond faster during reinfection?

Memory T cells respond faster during reinfection because they have previously encountered the antigen and are “ready” for activation. As a result, they require less stimulation, proliferate more quickly, and can rapidly produce cytokines or cytotoxic molecules to eliminate the pathogen.