T cells and B cells are the most critical components of the adaptive immune system. These cells are essential for fighting disease and play an important role in regulating hypersensitivity to harmless or “self” antigens.

T cells and B cells both recognize specific antigens via a complementary receptor, followed by activation and proliferation to specifically bind to the antigen of the infecting pathogen.

Despite the similarities between T cells and B cells, there are major differences in how they function within the immune system.

T cells are involved in cell-mediated immunity, whereas B cells are primarily responsible for humoral immunity (related to antibody production). In addition, the surveillance mechanisms of these two cell types are quite different. T cells recognize viral antigens outside the infected cells, whereas B cells can recognize the surface antigens of bacteria and viruses directly.

In this article, we will explore the role of T cells and B cells in detail, including cell formation, morphology, and function within the immune system.

Formation of T Cells and B Cells

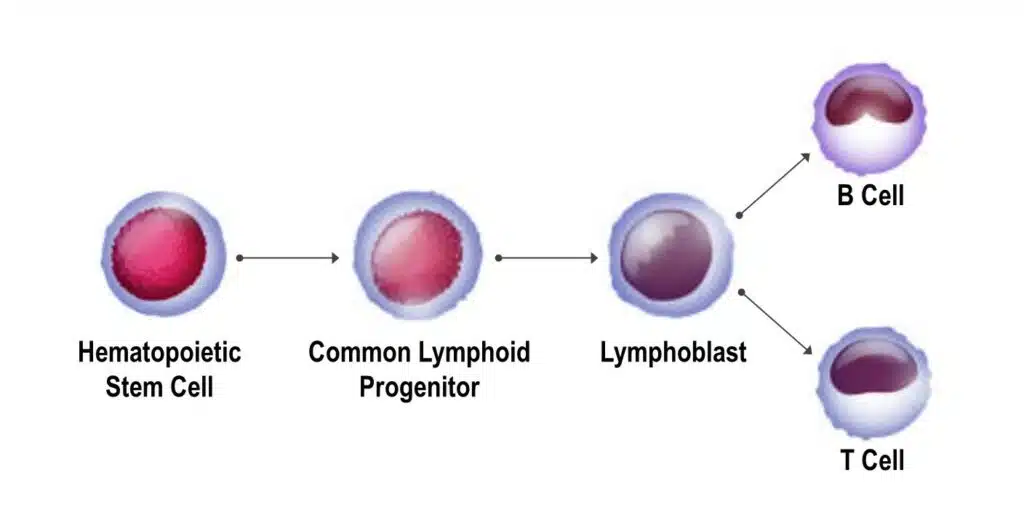

T cells and B cells originate from the same cell known as the hematopoietic stem cell, which forms in the bone marrow. Through differentiation processes, hematopoietic stem cells eventually form into B cells and T cells. The diagram below describes this process:

Following differentiation of the lymphoblast into either a T cell or B cell, the cells mature in different locations. T cells leave the bone marrow and migrate to the thymus for maturation (this is the reason they are called thymus-dependent, or “T”, cells). B cells, on the other hand, mature in the bone marrow or in the lymph nodes.

Morphology of T Cells and B Cells

T cells and B cells are morphologically difficult to differentiate because they are both small cells (approximately 8–10 microns in size) with a major nucleus containing dense heterochromatin and a cytoplasmic line containing a small number of mitochondria, ribosomes, and lysosomes.

All lymphocytes have antigen recognition receptors with a wide range of specificities on their surfaces. The genes that code for these constructions go through a progression of DNA recombination, giving T cells and B cells an expansive repertoire of antigen-specific receptors.

Role of T Cells and B Cells in Immunity

As mentioned earlier, T cells are mediators of cellular immunity and B cells take part in antibody production. Both processes are critical components of the body’s adaptive immune response. To understand how these cells work together to coordinate an effective immune response, it’s important to first cover the basic functions of each cell type.

B Cells and Humoral Immunity

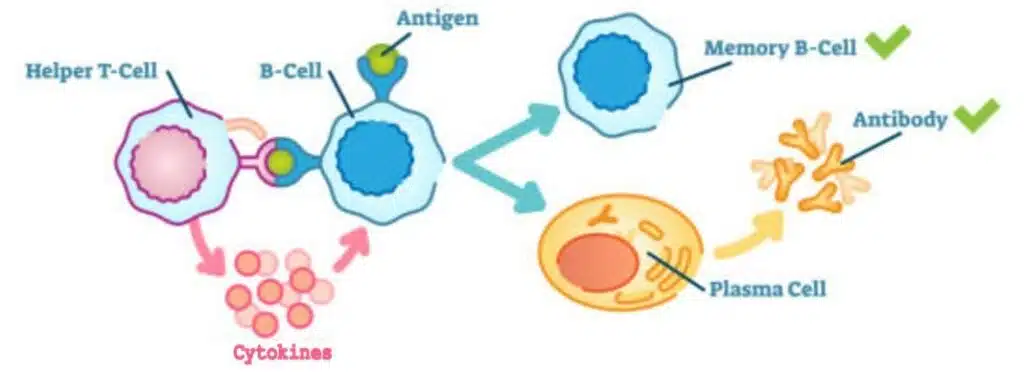

The main function of B cells is the recognition of antigens followed by differentiation into plasma cells which release antibodies to fight infection.

B cells, also called CD19+ B Cells, recognize foreign invaders such as bacteria through their surface receptors. After a B cell receptor binds to an antigen, the B cell engulfs the antigen through a process called receptor-mediated endocytosis.

The B cell then breaks down the antigen into peptides which are presented on the surface of the B cell. These peptides are attached to a special type of molecule called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II.

This process allows helper T cells, also known as CD4+ T cells, to recognize and bind onto the MHC class II. This binding by the helper T cells, in turn, releases cytokines.

Cytokines are important signaling proteins that trigger other B cells to proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells.

These plasma cells release antibodies that are specific to the antigen that was initially bound to the B cell in the first place.

T Cells and Cellular-mediated Immunity

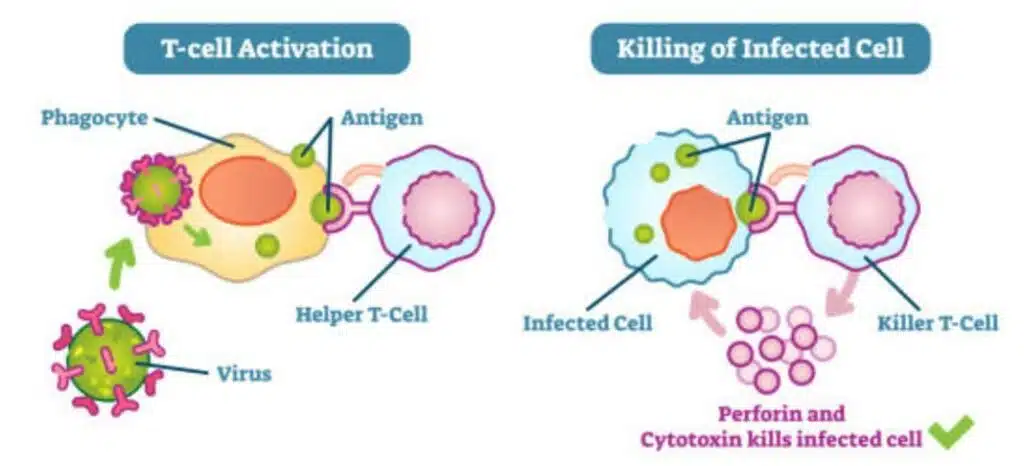

Now let’s cover the role of T cells in immunity. Similar to B cells, T cells are antigen-specific and divide rapidly when a particular antigen activates them.

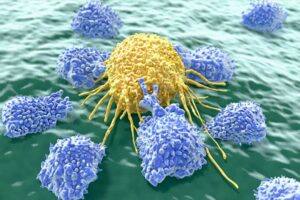

As discussed in the previous section, helper T cells release cytokines that direct the immune response. In contrast, cytotoxic T cells produce deadly granules that kill pathogen-infected cells.

The activation process of cytotoxic T cells (or CD8+ T cells) starts with a cell infected by a virus. This infected cell contains viral DNA and viral mRNA, and produces viral proteins and peptides. These viral peptides are presented by the MHC class I on the surface of the infected cell.

In this sense, the infected cell giving a warning signal to CD8+ T cells by showing the infected proteins on its membrane. CD8+ T cells recognize the viral peptides through their T cell receptors (TCRs) and secrete cytotoxins like perforin or granulysin which initiates programmed cell death.

Alternatively, cytotoxic T cells can kill infected cells through the Fas ligand pathway. Cytotoxic T cells express a homotrimeric protein called the Fas ligand which binds to transmembrane receptor proteins on the target cell. This binding alters the Fas proteins and induces cell death through a complex signaling process.

In addition to helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells, there are also memory T cells. There are many different types of memory T cells, but the main feature of these cells is they can quickly mobilize a specific immune response long after an infection has been eliminated. Memory T cells can convert into effector T cells very fast and attack a previously encountered pathogen.

Conclusion

T cells and B cells are part of a specialized network of immune cells that specifically respond to pathogens and fight off infections.

When a pathogen enters your body, our immune system responds in various ways to address the threat. These threats are hugely variable, so the immune response must be highly adaptable.

As such, immune cells such as T cells and B cells are required to fight infections in different ways.

B cells and helper T cells use the information gathered from the unique surface antigens on pathogens to trigger the production antibodies. Millions of antibodies cycle through the body and attack the invaders until the worst of the threat is neutralized.

T cells can also detect infected cells and use cytokines as messenger molecules to the rest of the immune system to ramp up its response. Cytotoxic T cells directly kill cells that have already been infected by a foreign invader.

When B cells and T cells identify antigens, they can use that information to recognize invaders in the future. So, when a threat revisits, the cells can swiftly deploy the right response to tackle it before it affects any more cells. That’s how you can develop immunity to certain diseases.

To learn more about this topic, check out our recent articles on T cell activation and the role of immune cells in preclinical research.